By Idris Jala

This blog is part of a DeliverEd Initiative series by policymakers and leaders from around the world who share their challenges in delivering reforms and reflect on the various approaches used to solve these challenges in their countries. The opinions contained in these blogs are those of the authors and do not reflect an official position of the Education Commission or its research partners.

DeliverEd aims to build the evidence base for how governments in low- and middle-income countries can achieve their policy priorities in education using delivery approaches.

The quest for how to radically improve the quality of education is a top priority for many governments around the world. Some have formed independent commissions and special task forces to develop recommendations for how best to improve education for all. Many of these commissions and task forces take a common point of departure in their methodology: what are the best practices of countries with high quality education and what can other countries learn from them?

Predictably, the recommendations focus on adopting best practices in areas such as curriculum, pedagogy, teacher training, and school facilities – but fail to focus enough on how to adopt these practices in the local context and the process of adaptation and implementation. As a result, many countries have failed to achieve the intended outcomes of radically improving the quality of education.

A new approach for Malaysia

In 2009, I worked as a minister in Malaysia to spearhead the government and its transformation work. I wanted to look for a fresh, alternative approach to implementation that could work in the local Malaysian context.

We developed a 7-step approach for education:

- Rank all schools in the country based on public examination scores over the last 10 years, using a simple spreadsheet to sort them from highest to lowest.

- Identify the top 1% highest-performing schools and inform them that they are the highest-performing schools in the country. Announce the rankings publicly and reward these schools.

- Form a special task force to study in detail why and how these schools have consistently performed well compared to the rest of the schools in the country.

- Develop a School Improvement Toolkit (SIT) which synthesizes the “best practice” methodologies of the top 1% schools in the country.

- Disseminate the SIT so all schools implement the practices as part of their annual school improvement plan, which forms the basis for how key stakeholders participate in the process to improve school performance.

- At the end of the year, rank all schools again. Ranking can be weighted; for example, 80% based on student examination results and 20% on other aspects, such as performance in interscholastic competitions like debates, performance arts, parental engagement metrics, and others.

- Publish and publicize the school rankings. This transparency will place greater accountability on the principals and teachers as parents and communities will put pressure on the schools to improve based on the published ranking.

In 2009, I convinced our prime minister and minister of education to adopt this delivery approach as an important feature of our National Transformation Programme on education.

Learning from high-performing schools

Malaysia is home to 10,202 primary and secondary schools serving 423,566 students (Ministry of Education, 2018). The top 1% highest-performing schools were those with excellent academic achievement, national and international awards, linked with other learning institutions, and run by highly capable personnel. They were not located only in affluent city centers; some were nestled deep in rural communities.

There were many misconceptions about why these schools performed better: maybe they had better facilities, or stronger curriculum, or better paid and supported teachers. But the high-performing and low-performing schools were nearly identical in all these aspects.

So, it begs the question: how did these schools make the top 1%? We found out there were four critical success factors that these schools had in common:

- Strong school leadership: Principals of these high-performing schools set high expectations that every teacher in their school follow the national curriculum strictly and devised methods for ensuring compliance. For example, Sri KDU in Damansara is a private school that followed the national curriculum. At the end of every school year, the principal requires teachers to return to school for 14 days during the holidays to prepare for the new year. All the teachers had their daily plans for the terms clearly laid out to comply with the national curriculum. The principal and his/her team checked these daily plans to make sure they were robust and of high quality. In short, the principals exercised leadership by insisting that their schools had excellent structured pedagogy for teachers to implement.

- Motivated, disciplined, quality teachers: Teachers in these top-performing schools were highly disciplined and focused their attention on implementing their daily teaching plan every single day of the year. They put on record simple notes in their “logbook” on how each day went and highlighted areas for improvement. This discipline of action was clearly a critical success factor. These teachers expected the principals or school inspectors to check these logbooks and reports and provide ongoing support.

- Parental involvement: Parents of the students in these top-performing schools demonstrated full commitment to their child’s education. Throughout the year, these parents made it their daily business to ensure that their children attended classes and completed their homework; they monitored their child’s progress and had regular dialogues with teachers regarding remedial work for improvement. One of the top-performing schools in Malaysia, SK Taman Megah (SKTM), was led by a passionate principal whose determination was to include parents. For every parent who had a complaint, she listened to find a resolution – and in doing so, drew them in to be part of the solution. Whether it was dealing with water shortages or power outages, their complaints were turned into opportunities for collaboration.

- Students’ desire to learn: At the epicenter of these critical success factors were the students themselves and their desire to learn. We found out that the principals, teachers, and parents in these schools injected a “contagion effect” to ignite a burning desire for learning amongst the students in these high-performing schools. In the case of Sri KDU, Sekolah Ulu Lubai, and SK Taman Megah, all three actors (principals, teachers, and parents) actively played their individual part in inspiring and encouraging their students to learn. School leaders acted as orchestrators, while the teachers and parents all joined hands to play their part in inspiring the students. When learning ceased to be a chore, it became a beautiful piece of music!

The answer to the question of how these schools became high performing became clearer: there was an alignment of the four constellations, comprising principals, teachers, parents, and students.

The positive impact of this delivery approach

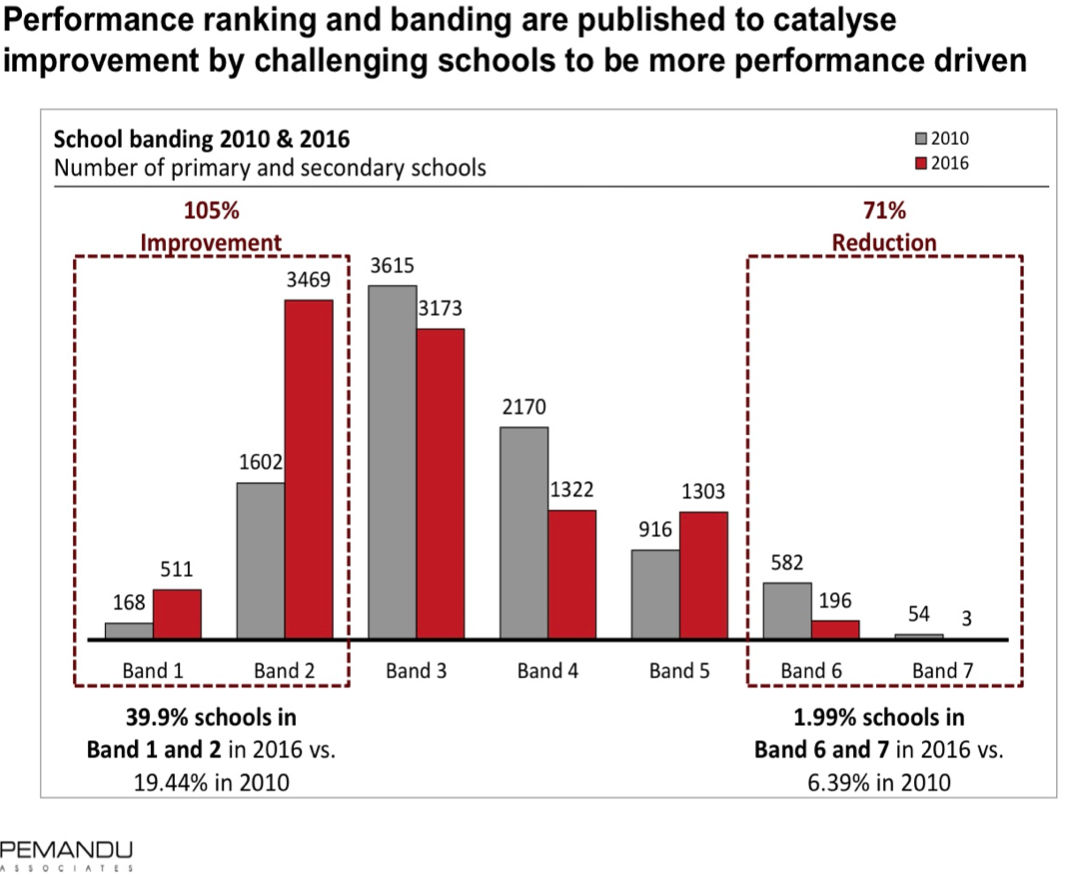

In 2010, when Malaysia started implementing this new approach, we placed the ranked schools in seven performance bands based on average student scores in public examinations. Figure 1 illustrates the number of schools ranked according to the seven bands.

At the beginning, only 20% of schools qualified in the top 1 and 2 bands. By 2016, there was a significant improvement, with nearly 40% of the schools in these top 2 performance bands. This represented a 105% improvement in school performance.

The impact of political transitions on successful delivery

Sadly, due to a change in government in 2018, this delivery approach was completely abandoned, and no rankings were done in subsequent years. A promising methodology which was simple, easy to implement, fit for purpose, and clearly showing results was discontinued simply because it was the legacy of the previous government when it could have also been the legacy of the new government.

A critical component of the DeliverEd Initiative’s research design not only focuses on the positive deviance measurements and looking at why high-performing schools are excelling and how a delivery approach can cultivate these practices in more schools, but it also examines the sustainability and longevity of delivery approaches – and if they continue amidst political transitions, how political signaling and sponsorship impacts the delivery approach’s effectiveness. I believe these findings will be important for all civil servants and leaders who are in search of fresh, new approaches to education in their own countries.

Idris Jala has a global reputation for rescuing ailing ventures or confronting difficult scenarios to turn around. He is steadfast in his belief that all organizations can lift themselves out of even the worst situations. During his tenure as CEO of the Performance Management and Delivery Unit (PEMANDU), he was tasked with spearheading the Malaysian Government’s transition towards high-income status by 2020. Prior to his role in government, Jala was CEO at Malaysia Airlines (MAS) for three years. He was brought on board to turn around the airline which was in crisis brought about by a prolonged bout of losses from operational inefficiencies. Before MAS, he spent 23 years at Shell, rising to hold senior positions including Vice President, Shell Retail International. In addition, Jala served on the Advisory Panel for the World Economic Forum (WEF) on New Economic Growth and on the Advisory Panel of the World Bank.

Idris Jala has a global reputation for rescuing ailing ventures or confronting difficult scenarios to turn around. He is steadfast in his belief that all organizations can lift themselves out of even the worst situations. During his tenure as CEO of the Performance Management and Delivery Unit (PEMANDU), he was tasked with spearheading the Malaysian Government’s transition towards high-income status by 2020. Prior to his role in government, Jala was CEO at Malaysia Airlines (MAS) for three years. He was brought on board to turn around the airline which was in crisis brought about by a prolonged bout of losses from operational inefficiencies. Before MAS, he spent 23 years at Shell, rising to hold senior positions including Vice President, Shell Retail International. In addition, Jala served on the Advisory Panel for the World Economic Forum (WEF) on New Economic Growth and on the Advisory Panel of the World Bank.