A new joint report with the Global Partnership for Education (GPE) maps existing tools and frameworks on teachers and the broader education workforce.

by Katy Bullard, GPE Secretariat, Ramya Vivekanandan, GPE Secretariat, Gabriele Goettelmann, Katie Godwin, Education Commission, and Amy Bellinger, Education Commission

(this blog was originally published on the GPE site)

As education access has risen around the world, the quality of education has become a top priority globally. The evidence is clear that effective teachers are key for student learning.

Increasingly, too, as governments and development partners have taken more of a systems approach to education quality, they have recognized the need to look beyond teachers to the broader education workforce that supports teaching and learning.

The Education Commission’s Education Workforce Initiative has been at the forefront of this shift, acknowledging that teachers are at the heart of the learning process but noting that increasing the number of teachers alone won’t be enough to ensure all children learn.

The pandemic has shown that teachers cannot work alone. Team-based approaches are urgently needed, where teachers collaborate with the wider education workforce, including school leaders, district officials and other support roles, as well as parents and the community, to reach all children.

A new report to map existing tools and frameworks

GPE promotes a systems transformation agenda, which requires attention to roles throughout the system, including and beyond teachers.

For GPE partner countries, effective education planning and systems change require insight into the broader education workforce. Diagnostic data are essential for this, and partner countries have expressed a strong need for better understanding of and improved access to tools that can generate such data.

To this end, GPE conducted a mapping of existing diagnostic tools and frameworks on teachers and the broader education workforce.

This work, which was undertaken in close collaboration with the Education Commission, responds to the need expressed by countries for enhanced understanding and access to such tools and frameworks, providing a roadmap to guide countries and development partners in selecting tools relevant to their contexts.

More broadly, it supports and feeds into the potential future development of a diagnostic tool for supporting education workforce design and development. Such a resource is also a priority action area for the Global Education Forum’s Education Workforce working group, which is co-led by GPE.

Findings of the mapping

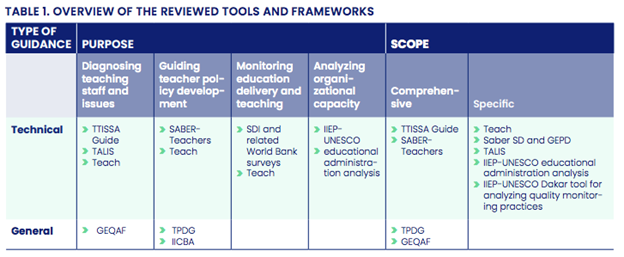

The mapping found that existing tools vary in the type of guidance they offer (technical or general), purpose (for diagnosis, guiding policy development, monitoring delivery/teaching, analyzing organizational capacity) and scope (comprehensive or specific).

Critically, the mapping found that existing tools and resources are already making useful contributions and could be built into a future consolidated diagnostic tool. Available tools offer guidance on:

- collection of teacher data (e.g. the TTISSA Guide, developed by UNESCO)

- policy development (e.g. the Teacher Task Force Teacher Policy Development Guide)

- analysis of how teaching happens (e.g. the World Bank Teach tool and the OECD TALIS)

- exploration of collective or organized action (an IIEP-UNESCO Dakar tool for analyzing quality monitoring practices, available in French only).

All these tools are critical for supporting countries to inform their policies and processes related to the education workforce. Ministry officials and other professionals involved in sector planning and reform may be able to build on the methodological guidance that the tools offer.

That said, most tools focus only on teachers. In some rare cases, tools consider other education personnel (usually school leaders), but even then, rarely look at how the different roles supporting teaching and learning are organized and interact or examine how workforce policy is implemented to improve teaching and learning.

The mapping also found notable challenges in how existing diagnostic tools have been implemented.

In many cases, stakeholders were unsure which tools could be useful for their contexts. Even where tools are being used, the expertise and resources – not only financing but also human capacity and time – to effectively implement them were limiting, complicating their use.

Even so, there is strong demand for education workforce diagnostics, both nationally and internationally. Such diagnostics could be valuable tools if coupled with training and support to guide their use.

Looking ahead: filling identified gaps

The mapping will be shared with GPE partner countries and development partners, all of whom have a role to play in building the education workforce and transforming education systems. The paper can help ministries of education make more intentional choices about which diagnostic tools to use and when.

Beyond this, the mapping also raises useful considerations about what a future diagnostic workforce framework could and should do. Such a resource may provide guidance on how to select and adapt relevant tools for a given context and as needed, fill in the gaps not covered by existing tools, including comprehensive analysis of the broader education workforce and organization of workforce roles.

Future diagnostic frameworks, linked to sector analyses and other sector planning tools, should be collaboratively developed and include participatory research approaches. Such tools could be a valuable resource for countries working to improve learning by better supporting the broader education workforce.