Arua, Northern Uganda — We are on Uganda’s northern border with South Sudan. A beautiful area with rolling green hills scattered with small villages comprised of mud huts, mango trees and compact cotton and tobacco fields. As Chief Adviser to the Education Commission, I am travelling with Save the Children UK’s team including the CEO, Kevin Watkins, on a joint mission to discuss schooling for South Sudanese children and youth seeking refuge in the North of Uganda. These concerns are in addition to the existing challenges facing Uganda’s own educational efforts.

The Commission’s Pioneer Country Initiative was launched in Uganda late last year when a delegation headed by former President of Tanzania, H.E. Jakaya Kikwete, met with Uganda’s President H.E. Museveni. Save the Children and the Education Commission are working together to bridge the gap between short-term humanitarian responses and longer-term development in education. Today, Save the Children is providing emergency schooling to refugees across Uganda, top up classes for those who have fallen behind, and play camps that help children recover from their trauma.

The work that Uganda, with support from humanitarian partners like Save the Children, is doing with refugees is of enormous importance. This is because while neighboring South Sudan gained independence in 2011, it did not gain peace. Today the country is faced with both conflict and famine, and the immediate future is of grave concern. The UN has warned that the conflict could slide into genocide, while at the same time more than half the country now faces mass hunger. As a result, nearly one million South Sudanese refugees have entered Uganda. The sheer size of these numbers is difficult to comprehend. But what is clear is that this is one of the world’s biggest humanitarian crises.

Gradually, the landscape changes. The huts are replaced with small tent dwellings made from white plastic emblazoned with “UNHCR.” We have arrived at the Imvepi refugee settlement. A few miles further down the bumpy laterite road, we reach the settlement’s reception centre. The first thing that strikes me is the sheer number of people. Today there are more than ten thousand people at the centre – individuals who have traversed the long road to Uganda from South Sudan. And more than 3,000 people arrive every day. It takes a Herculean effort to keep up with the surge.

At the reception centre, I meet Rose*, 16, and her younger sister Victoria*. They have travelled from South Sudan on their own. “Walk straight down this road and eventually you will reach Uganda,” their parents told them. It took the sisters four days, and here they sit now in the centre’s unaccompanied minors section. Victoria tells me the schools are no longer functioning in South Sudan and she must continue her education. I have three daughters – no way can I ever imagine the parents’ pain letting these two beautiful girls venture alone on that treacherous road to Uganda in search of hope in the form of an education.

We move on to the Rhino Camp resettlement area, home to 86,000 people covering ten square miles. I meet Anni* and her 12 year old daughter, Sylvia*, who have been here since November 2016. They fled fighting in South Sudan. Sylvia is back in school as part of Save the Children’s accelerated learning programme at Ariwa school.

Anni explains that her neighbours were captured and slaughtered as they slept. It took her five days to reach the border. It was then that her husband was killed in front of her. Anni adds they wanted to kill her baby. “I told them, if now, if you want to kill my baby, it is better for you to kill me together. They got my baby and hung the baby facing down and they were holding a knife. I started calling Jesus name, be with me.” Her baby was spared.

Determined to keep her daughter in school, Anni does not have the money to pay for the small fees. “The importance of education is that, if you are learned, the little information you got will empower the child to be independent, to be self-reliant, to be able to handle issues and to be able to sit well with others.” Anni adds that if children do not go to school, “…they will be like town dogs who roam.”

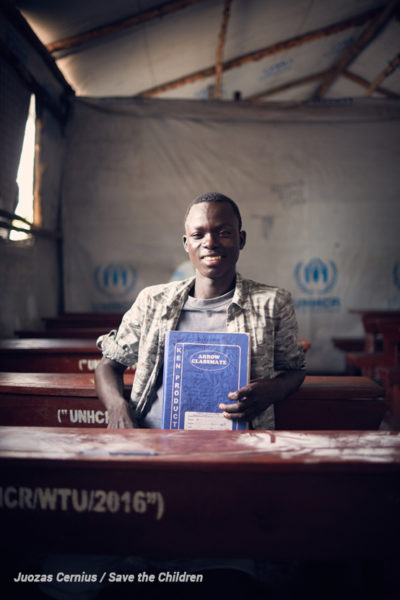

The next day we visit another settlement, Bidi Bidi, the largest in the world with around 270,000 people. Here I meet David*, a budding scientist and top of his class in South Sudan. He is sitting at the back of the class quietly reading his book when I approach him. I ask if I can look through his large blue hardback exercise book. His face lights up. He shows me with pride the work he had been doing at school in South Sudan. “I want to be a scientist” he explains to me. On that long journey from South Sudan, most people brought nothing but themselves. David, however, clung to his book and a desire to learn in school.

David with his school book from South Sudan.

During our time in Uganda, we meet many more refugees. Their stories are disturbing, journeys horrific, and futures unknown. But coursing through the settlements and country is something not seen but rather felt: Uganda’s compassion and empathy towards the South Sudanese refugees. In a world where refugees are increasingly vilified and in a region under great stress, this compassion and empathy is both humbling and uplifting.

Northern Ugandans have their own history of being uprooted and displaced. Even as recently as 2003-2012, 95% of the population – some 1.8 million people – were internally displaced. Throughout our delegation trip, we come face-to-face with the expression of Ugandan compassion and empathy. From the teacher at Kiranga primary school, a doctor at Ariwa health centre, the government official in Arua, the Minister of Education and the Minister of Finance. The list goes on. And this deeply felt compassion has resulted in an incredibly progressive policy towards refugees – one of the best in the world.

Now Uganda needs help to sustain this policy. On the June 22, the President of Uganda, H.E. Museveni, is hosting a summit in Kampala designed to ask countries to help Ugandans assist the refugees and host communities. Other world leaders will be attending, including UN Secretary-General Guterres.

A spotlight must be shone on education for refugees and host communities. At this conference, a plan will be presented setting out how much money leaders need to pledge in order to ensure all refugee children are in school. The Education Commission is working with the Ugandan government to develop a plan to deliver an education to all Uganda’s children – whether refugees or citizens – a roadmap that will outline results and ramp up delivery.

And so for refugees in need but with incredible resilience, host-communities under pressure but offering a welcome hand, and a region gripped by uncertainty but full of potential, now is precisely the moment to deliver that most fundamental right to an education.

*At a name’s first appearance indicates it has been changed.

Caroline Kende Robb is Chief Adviser to the Education Commission. This article can also be viewed on Huffington Post here and the World Economic Forum Blog here.