The discussions in Pakistan around who is in and who is out – who learns and who does not – are getting louder. And so they should, as we now have a mounting burden of unmet milestones that are piling high. Almost six years have passed since education was declared a fundamental constitutional right with the insertion of Article 25A in April 2010, courtesy of the 18th Amendment. But indicators continue to highlight that the poorest citizens are the most excluded – girls remain the most marginalized, especially the poor and disabled.

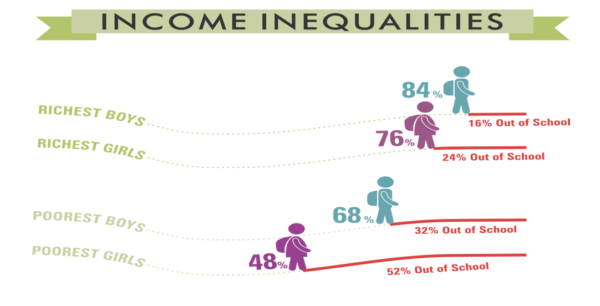

Every year, the citizen-led large-scale household based assessment collected by ASER Pakistan highlights such exclusions based on geography. Of 258,021 children aged 5-16 years-old surveyed in 83,755 households across Pakistan’s 146 rural and 21 urban districts by ASER in 2015, 68% of the poorest boys were enrolled in school, while only 48% of the poorest girls were in school.

Figure 1:

On 25 September 2015, the Government of Pakistan became one of the 193 country signatories to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The fourth SDG calling for “inclusion and equity” in education highlights the urgent need for governments and citizens to push for robust data and evidence on who is in and out of schools, and who learns and who does not. In this context, ASER data provides an important baseline for tracking this SDG using equity benchmarks.

Against such a backdrop, the research program on Teaching Effectively All Children (TEACh) is a timely initiative providing evidence on effective teaching strategies to raise learning for those at risk of being left behind. Last month, at a roundtable on “Teaching Learning and Disadvantage” hosted by the Institute of Development and Economic Alternatives (IDEAS) and the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre at the University of Cambridge, some 20 participants discussed emerging findings from the TEACh research. The senior representative from the Government of Punjab’s School Education Department confessed there is little understanding of the learning needs of children with disabilities within the mainstream schools, let alone counting such children who are in school or planning for them in the teaching and learning processes.

In Punjab, exclusion is addressed by the separate Special Education Department established in 2003-4. At its inception, coverage included 51 schools reaching out to 4,265 children, increasing to 248 institutions across the province catering to 28,850 students with disabilities in 2016. But is that sufficient? The Special Education Department is providing many facilities but with limited education provision. They are now looking at alternative models. There are plans this fiscal year, in collaboration with the Punjab Education Foundation (PEF) working with low-cost private schools through vouchers, to launch an inclusive education initiative catering to children with mild disabilities. However, robust approaches to identifying those with mild disabilities are not yet in place. The commitment gap by the government is also telling. For a population of more than 100 million in the province, and a disability rate of approximately 5%, the budget provisions for the Special Education Department for the current fiscal year are under Rs. 1 billion compared to more than Rs. 312 billion for the broader education sector. Clearly more can be done.

What is critical in creating a spectrum of choices is the government’s resolve for ensuring the Constitutional Right to Education. In 2014, the Government of Punjab passed the Punjab Free and Compulsory Education Act 2014. In Articles 2(c) and 2(d) and 3 (4), the Act stipulates definitions of what constitutes disadvantage, education and suitable education.

- Article 2 (c) “disadvantaged child” means a child who belongs to a socially and economically disadvantaged class, or to any other group having disadvantage owing to social, or such other reasons or who belongs to such a parent whose annual income is less than the limit which the Government may, by notification, specify;

- Article 2 (d) “education” means teaching and training of mind and character by attendance in regular school education, madrassa education, vocational training and special education in the classroom and school setting, or non-formal education or the education prescribed for a child or category of children by the Government;

- Article 3 (4): The Government shall, in the prescribed manner, provide or cause to be provided suitable education to a child suffering from disability or a special child.

It is reassuring to see this legal backing as we build choices for what must be done for all children in Punjab, and Pakistan more broadly. Similar acts exist in Sindh and Balochistan provinces, and it is essential to track the progress of these national commitments, together with global accords made as part of the SDGs.

To contribute to this evidence collection, in 2015 ASER collected data on learning for children affected by disabilities from 21,512 households covering 60,000 children in all 36 rural districts of Punjab. The instruments were based on the Washington Group Short Survey Questionnaire, with adaptations based on UNICEF-MICS. The tool covered a child’s functioning in six areas – sight, hearing, mobility, self-care, speech, and memory – taking account of their use of any aids such as spectacles, hearing and mobility aids.

The findings revealed that 1.2% of children were reported as having a moderate to severe difficulty in seeing, hearing, walking, caring, understanding or remembering. Compared to the 78% enrolled in schools not affected by disabilities, 70% of children with moderate to severe disabilities were enrolled. Wider gaps were apparent for learning, however. Whilst there is surprisingly little difference between children with mild disabilities, the real challenge lies for children with moderate to severe difficulties. For example, 60% of children reported to have moderate/severe difficulties were unable to read letters (i.e. the beginner stage) compared to 14% who had no difficulties or mild difficulties.

The International Commission on Financing Global Education Opportunity’s recent report, The Learning Generation: Investing in education for a changing world, proposes four powerful transformations to get all young people into school and learning within a generation. Inclusion is one of these top transformations promoting more targeting of efforts and resources at those at risk of not learning. The sheer number of out-of-school children with disabilities only serves to underscore the critical need for inclusion. The Commission estimates that as many as half of the estimated 65 million primary and lower secondary-school age children with disabilities in developing countries are out-of-school. Alongside expanded financing to ensure education is delivered to those with disabilities, the Commission recommends that leaders adopt progressive universalism to guide more equitable expansion of education opportunity. In delivering a universal and quality education, the needs of the disadvantaged should be prioritized. Tackling the root causes of educational exclusion cannot be achieved by governments or the education sector alone. To address this, the Commission recommends more cross-sector cooperation as well as a greater role for communities, non-state actors and innovation. Community action is vital to challenge norms and support local change, whether through advocacy to expand learning opportunities for the disabled or to change legislation. Increasingly, technology is transforming the inclusion of children, from e-learning that allows for flexible learning in flexible locations to scaling up low-cost measures such as glasses, hearing aids and large print books that make it possible for children with visual or hearing impairment to learn in mainstream schools alongside their peers.

Analysis of ASER data, as well as other citizen-led assessments by the REAL Centre, contributed evidence in support of this message. As a Commissioner on the Education Commission, it is my mission to mobilize Pakistan to become a Pioneer Country – a country that is unafraid to invest in education and then ensure return on investment through performance reforms to deliver results, innovation strides to adapt to future needs, and inclusion efforts to ensure no child is denied that most fundamental right to an education. And so I hope Pakistan will embark on a journey to include the excluded and ensure higher allocations to education, ultimately reaching 6% of GDP as outlined in the Learning Generation vision.

For Pakistan, there is scope to go further still in generating statistics that capture educational inequality, especially as it relates to those with disabilities. Recognizing this data, and then acting upon it, is the most powerful way to hold governments accountable when it comes to addressing the needs of all citizens. The time for such education action is now.

Baela Raza Jamil is an Adviser/Trustee at Idara-e-Taleem-o-Aagahi (ITA) and is a Commissioner on the International Commission on Financing Global Education Opportunity.