It is a hot and steamy morning in Abidjan, a bustling West African city in Côte d’Ivoire, nestled along the beautiful Gulf of Guinea flowing into the Atlantic Ocean. An enclosed lagoon weaves endlessly throughout the cityscape.

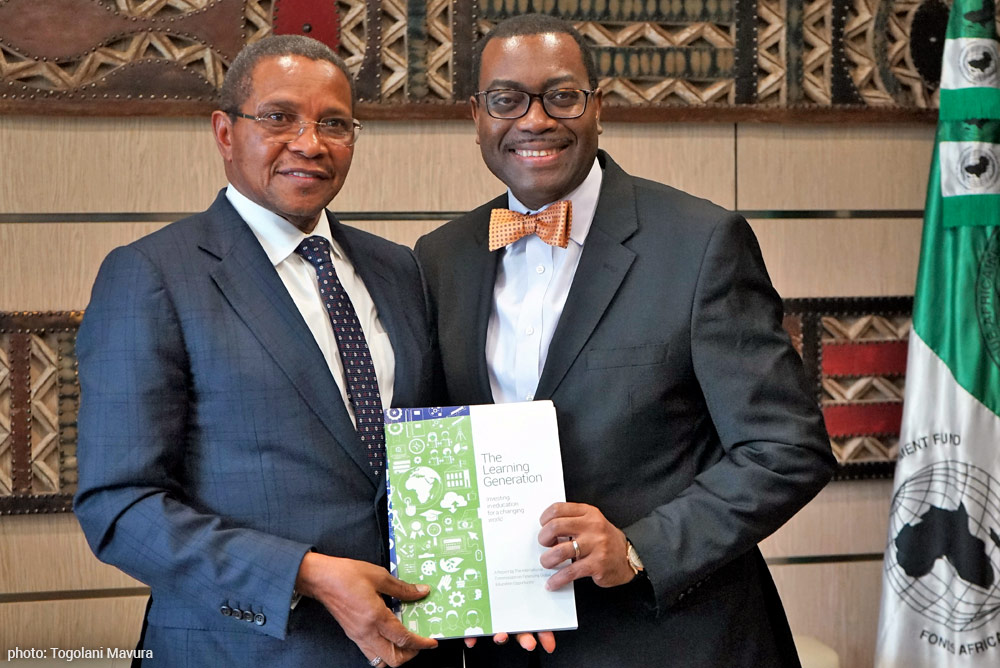

We are here in Abidjan as part of the Education Commission’s dialogue with heads of state and government across Africa to present the Learning Generation report and share ideas. The mission is led by our Commissioner H.E. Jakaya Mrisho Kikwete, the former President of Tanzania.

On our agenda are meetings with President Ouatarra of Côte d’Ivoire, a highly respected economist and former IMF Director, and President Adesina, the inspirational head of the African Development Bank.

History, culture and education

To understand the education and culture in Côte d’Ivoire, we must keep in mind a fact that many of us forget: people have been migrating for thousands of years. Côte d’Ivoire is no stranger to these trends as it is a land on the move with ever-evolving demographics and diverse cultures.

- In early Roman times, caravan traders established routes across the Sahara from northern Africa to Côte d’Ivoire searching for gold, salt and slaves.

- Over the years, kingdoms created by various peoples emerged and went. Oral histories tell us that the Mandinka people migrated from the Niger basin to the coast during the 1300s. I lived in The Gambia for many years and speak Mandinka so this fragment of history resonates with me.

- What followed was several hundred years of relatively centralized, hierarchical kingdoms and decentralized societies organized around kinship lineages with those in the north being linked to Muslim kingdoms.

- In the early 15th century, Portuguese explorers were the first Europeans to reach the coast; they initiated trade in gold, ivory and pepper and later slaves. The French followed.

- The country became a colony of France in the late 1800s and finally achieved independence in 1960. Stability followed and for many years Côte d’Ivoire boomed.

- From The Gambia in the 1990s, we viewed Abidjan as the shining capital of West Africa. Some even called it the Manhattan of West Africa.

Then from 2001, a near decade long crisis devastated the country, the schools and the children. By 2010, more than one million students were out of school.

Fragility with opportunity

Today, however, Côte d’Ivoire is booming again with one of the highest growth rates in Africa (nearly eight per cent GDP growth in 2016) – a remarkable achievement considering the unfavorable global and regional context. The country is the world’s largest exporter of cocoa beans, and its citizens enjoy a relatively high level of income compared to other countries in the region.

As is often the case, this growth has left many citizens behind with access to education far from universal. Many Ivorian children are not learning, and others who are in school perform below the average in reading and mathematics. At the end of primary school, too many children still cannot read or write properly. Indeed, children here spend on average only eight years in the classroom while pupils in emerging countries spend almost double (14 years). This gap is widening over time, while the quality of education has deteriorated. Children from the richest 20 per cent of families consume four times more resources in the education system than those of the poorest 20 per cent. Learning outcomes are lower in the north of the country than in the south, and rural areas have lower learning outcomes compared to urban areas. (See more details here)

The system is inefficient and dropout rates are high. Over 90 per cent of public funds are spent on staff salaries, subsidies to private schools and administrative costs leaving little for anything else. With a young and growing population, education planners ought to be alarmed: the number of students will grow from over five million today to nearly 14 million in 2030. More teachers, more classrooms, more money and the better use of existing funds are all urgently needed.

Urgency and commitment

We learn from President Ouatarra that the political commitment for education reform is high and the need urgent. Côte d’Ivoire spends 20 per cent of its budget (5 per cent of GDP) on education, making the country one of the biggest education spenders in Africa. Ambitious targets have been set, President Ouatarra outlines for us, and provision of free education until the age of 16 has been introduced. Universities are being built in each region. Reforms are in place to scale up enrollment, especially in secondary schools and vocational training. Programs to boost learning in the early years are now in place.

A recent report from the World Bank laid out the case for rethinking subsidies to private schools and introducing performance-based pay for teachers. Making expenditures more efficient and providing better skills for young people to get jobs are a priority in this country where unemployed youth can give rise to social unrest. But reforms are tough. During our visit, the teachers went on strike.

Educational advancements are achievable. Countries such as South Korea and Malaysia are success stories in transitioning to emerging markets status thanks to their investments in building some of the best education systems in the world. President Ouatarra has a vision, and modernizing education for tomorrow’s world is part of it.

Our next stop was the African Development Bank, headquartered in Abidjan, to meet with President Adesina. “There are nearly 696 million children and youth in Africa, representing 60 per cent of its total population. These millions could ignite a new age of inclusive growth and prosperity on the continent – if carefully cultivated through education,” President Adesina has stated. He explained more must be done for Africa, across all types of education, and especially post-primary levels – TVET (Technical, vocational, education and training) and higher education. He strongly believes that partnering with the private sector and other development partners is vital.

Next steps

For Côte d’Ivoire, reforming education is expensive. The Education Commission is supporting ongoing work in selected Pioneer Countries and connecting with development partners and international organizations to bring in additional assistance, including through the Commission’s proposed International Finance Facility for Education (IFFEd) – a partnership between developing countries, multilateral development banks, and public and private donors dedicated to mobilizing and multiplying new resources for education in low- and middle-income countries.

Not reforming education will be even more expensive. In this beautiful, vibrant country of such promise, fragility and opportunity walk hand-in-hand. The transformation cannot wait. With astute political leadership, reforms and wise investment, achievements in education can be unlocked.

Feature photo: Commissioner H.E. Jakaya Mrisho Kikwete, the former President of Tanzania presents the Learning Generation report to President Adesina of the African Development Bank.