By Gwyn Bevan

This blog is part of a DeliverEd Initiative series by policymakers and leaders from around the world who share their challenges in delivering reforms and reflect on the various approaches used to solve these challenges in their countries. The opinions contained in these blogs are those of the authors and do not reflect an official position of the Education Commission or its research partners.

DeliverEd aims to build the evidence base for how governments in low- and middle-income countries can achieve their policy priorities in education using delivery approaches.

My experience with the Prime Minister’s Delivery Unit (PMDU) in England focused on how the Department of Health managed the performance of the English National Health Service (NHS) to deliver the PMDU’s targets for reducing wait times for hospital care. At the time, the UK government committed to increase spending on the NHS in England by 5% a year (in real terms) for five years. Before 2000, hospitals that failed to meet targets for reducing wait times were rewarded with extra funding. But under the “star-rating” regime introduced after 2000, this radically changed: chief executives of hospitals deemed to have failed to hit targets were at risk of losing their jobs (known as “targets and terror”) and their hospitals were given zero stars and publicly named and shamed as failing.

From 2000 to 2003, I was the director at the Commission for Health Improvement (CHI), the quality regulator of the NHS in England and Wales. I was responsible for CHI’s role in the development of the star-rating regime, where my overriding concern was to ensure that our assessments of a hospital’s capacity to oversee clinical quality were not given secondary importance to meeting the targets established for wait times.

Following devolution in 1999, the governments in Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland no longer had to follow the UK government in its decisions for England on funding and governance of each NHS. Each country decided to match England’s generous increases in funding in each NHS from 2000 and set targets to reduce hospital wait times. However, these countries also continued to reward hospitals that failed to hit targets with additional funds, which England decided not to do. This gave me a ringside seat in the extraordinary natural experiment to test whether the PMDU made any difference in reducing wait times in England and Wales.

The first set of star ratings was published in the autumn of 2001. Soon after, I went to a series of grim meetings with officials from the Department of Health and the chief executives of the 12 zero-star-rated hospitals (described in the media as the “dirty dozen”). All executives were at risk of losing their jobs – six eventually did. This shock therapy convinced those working in the NHS in England that there had been a fundamental change in the system. Through learning by doing, in subsequent years the Department of Health in England learned that it did not need to stay directly involved in firing the chief executives of “failing” hospitals. This was because publishing the star rating in national and local media had a powerful enough effect and impact on the reputations of each hospital and their staff.

Publication had a devastating impact on zero-rated (failing) hospitals and troubled the “falling stars” – hospitals that lost stars from their rating. One chief executive, whose hospital was demoted from three stars to two stars, told me that what troubled her most was that the demotion would be prominently featured in the local newspaper. Star ratings created powerful incentives for zero-rated hospitals to improve their performance to avoid the same fate the following year and for falling stars to improve and regain their lost star(s).

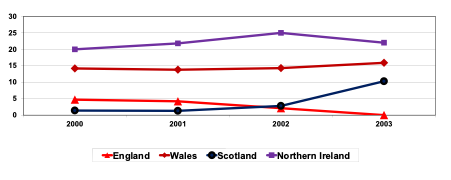

Figure 1 shows the percentages of patients waiting more than 12 months in each country of the UK as each NHS was allocated generous increases in funding. England’s NHS hit the PMDU’s target of 0% of patients waiting more than 12 months for hospital admission by 2003. In the other UK countries these percentages increased.

Figure 1: Percentages of patients waiting more than 12 months for elective admission to hospitals in UK Countries (2000-2003)

Reasons for England’s success and Wales’ challenges in delivery of reforms

The Auditor General for Wales investigated why hospital performance in Wales deteriorated whilst it improved in England. His critical 2005 reports highlighted the absence of several critical components in the delivery process in Wales: the government had set too many targets, failed to make clear which should be prioritized, and lacked effective monitoring of performance. The report also illuminated perceptions in the NHS that the government rewarded failure to meet targets and it lacked ambition for the NHS’s performance. In Wales, the target for total wait times for hospital admission after being referred by a general practitioner for an elective operation was three years in 2005; in England, the NHS was on track to hit the target of reducing total wait time to under 18 weeks by 2008.

…in Wales: the government had set too many targets, failed to make clear which should be prioritized, and lacked effective monitoring of performance.

Two individuals were vital to successful delivery in England. The first was Tony Blair, who brought with his authority as prime minister a commitment to find time for monthly stocktake meetings with ministers and officials. This sent the most powerful political signal to all involved of the importance of the PMDU and its operations. The second, Michael Barber, was PMDU’s inspirational leader and trusted by ministers and officials. The PMDU became the most exciting place to work in government with its mix of talent: officials who knew how government worked and staff recruited from consultancies who brought different ways of thinking and fresh, innovative approaches.

What others can learn from the UK’s PMDU

While studying innovations in government over several decades, I have found that most initiatives have, at best, minimal impact on the way services are experienced by their users. The PMDU is an exception, which explains why focusing on delivery has becoming increasingly attractive to governments around the world.

Michael Barber’s Deliverology 101 outlines the five key components of deliverology: developing its foundations, understanding the challenge, developing plans, driving delivery, and creating a culture so its achievements become irreversible. Deliverology is an exemplar of a well-designed socio-technical system that combines the developments of a sound technical basis with a distinctive social organization to deliver transformational change in performance. The DeliverEd Initiative seeks to generate evidence on how the core functions (such as setting targets, measuring and monitoring these targets, creating learning and accountability systems, etc.) and design choices of a delivery approach impact its effectiveness as well as how developing leadership at all levels of the system work to deliver transformational change.

In England, deliverology could focus on improving literacy and numeracy without the obstacles many other countries face, such as a shortage of qualified teachers, teacher absenteeism, and low girls’ enrollment rates. Deliverology in these countries must begin by tackling these obstacles. A natural focus of DeliverEd’s research on the effectiveness of various delivery approaches is how appropriate the design features and choices are for remedying different kinds of delivery challenges. Research also needs to establish whether there was a prerequisite for success, namely strong consistent support from ministers and other political leaders. This vital support cannot be guaranteed because it brings three different kinds of costs:

- Creating hostages to fortune: public admission that existing performance is unsatisfactory (easier for a new government); and publishing ambitious targets, which define what are hoped to become acceptable standards of performance, with the downside risk that improved performance that falls short will be seen as failure.

- The time required for regular stocktake meetings by a heavyweight politician to energize those at the heart of government and meet those who have delivered new benchmarks in performance on the front line.

- Withstanding the backlash from being seen to “flog” teachers by implementing a system with sanctions for those who fail to deliver the new norm of acceptable performance. (In 1999, Tony Blair famously warned: “You try getting change in the public sector and public services – I bear the scars on my back after two years in government. Heaven knows what it will be like if it is a bit longer.”)

Join us.

Gwyn Bevan is Emeritus Professor of Policy Analysis in, and former Head of, the Department of Management at the London School of Economics and Political Science and is an Affiliate Professor for the Istituto di Management of the Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna, Pisa. As Director of the Office for Healthcare Performance at the Commission for Health Improvement (2001 to 2004) he was involved in the transformation of the performance of the National Health Service (NHS) in England and observed its absence in Wales. This led to research into the natural experiment on how differences in policy between the countries of the UK following devolution impact on outcomes. He has served on advisory committees to Secretary of State for Health in England, the Welsh Office, the Lord Chancellor’s Department, the Department of International Development, Her Majesty’s Inspector of Constabulary, and the Assembly government of Wales.

Gwyn Bevan is Emeritus Professor of Policy Analysis in, and former Head of, the Department of Management at the London School of Economics and Political Science and is an Affiliate Professor for the Istituto di Management of the Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna, Pisa. As Director of the Office for Healthcare Performance at the Commission for Health Improvement (2001 to 2004) he was involved in the transformation of the performance of the National Health Service (NHS) in England and observed its absence in Wales. This led to research into the natural experiment on how differences in policy between the countries of the UK following devolution impact on outcomes. He has served on advisory committees to Secretary of State for Health in England, the Welsh Office, the Lord Chancellor’s Department, the Department of International Development, Her Majesty’s Inspector of Constabulary, and the Assembly government of Wales.