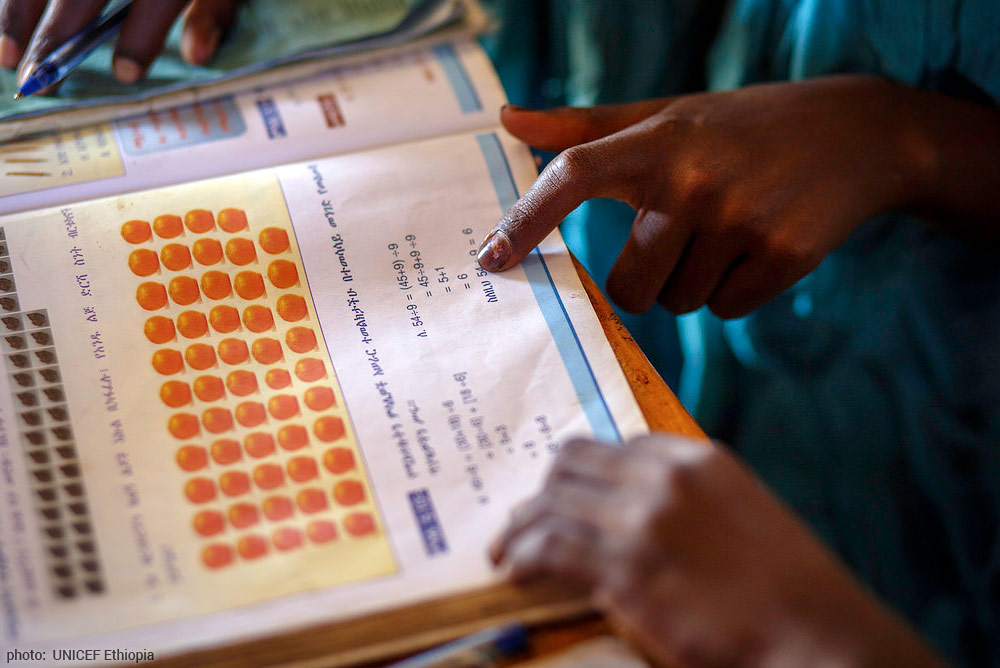

Many countries in Africa are now promoting the teaching of local languages in schools and using them in curricula instead of foreign languages, such as English or French. Teaching local languages is beneficial to children since it allows them to begin their education in a language that they can understand and speak rather than subjecting them to learn to speak, read and study a language they are not familiar with.

In addition, African languages have another benefit for learners: almost all the local languages spoken on the continent have a transparent orthography, meaning the connections between the speech sounds and written letters are consistent at grapheme-phoneme level and the rules of the writing system are thus easy to understand. Since there is just one letter (or letter combination, grapheme) for each speech sound, learning the connections of spoken and written items makes it possible to read all the words in that language soon after the sounds of letters have been memorized. Easier and faster learning of letter-sound connections allows for quicker word reading and therefore quicker reading fluency and comprehension. Thus, education in local languages and specifically teaching literacy in local languages in African schools could make it easier for the children to reach reading comprehension skills earlier.

However, this does not happen unless teachers have the right training for teaching literacy in local African languages. The challenge in teaching literacy in local languages in African schools is that in many African countries the teachers themselves went to school during periods when English or French was used as the language of instruction. In particular, English is one of the most difficult alphabetic languages to learn even for a native speaker. And despite the complexity of English orthography where practically none of the letters represent the same sound everywhere, it also happens to be the dominant language in literacy research. This means that most of the information and research that is currently available about literacy learning is based on the English language and is not applicable to African languages. More emphasis on building good literacy skills in local languages could help many children to stay in school and learn more.

Literacy instruction programs should be designed with the goal of making the learning process as easy as possible for the learner. And indeed, teaching local African languages rather than foreign languages can make learning to read much easier for students in Africa. Mobile technology, such as learning games, can provide additional support to learners, especially if students are able to access digital libraries of local language texts without charge as they learn to read, especially in countries where exciting reading materials for children have not previously been available.

Since most of what we know about learning to read and teaching literacy is still based on learning the English language, it would be extremely beneficial to provide more resources and funding for African academics, teachers and scholars to conduct research on literacy and learning in African languages. More foundational research and knowledge is needed so that African schools and schools systems can better develop education programs that promote use of local languages for reading instruction.

Professor Heikki Lyytinen, University of Jyväskylä, Finland, UNESCO Chair of Inclusive Literacy Learning for All with Francis Sampa, Zambia; Pamela February, Namibia; Taimi Nghikembua, Namibia; Flora Malasi, Kenya; Stella Damaris Ngorosho, Tanzania; Christopher Yalukanda, Zambia; Jacob Chomba Nshimbi, Zambia and Emma Ojanen, Finland.